1. To start off, could you tell us a little about your background and what led you into researching women’s health and Type 2 diabetes?

I’m a Senior Research Fellow at UNSW in Sydney, and most of my work sits at the intersection of women’s health, ageing, and health equity. I look a lot at how we actually support people in real communities, not just in theory, and not just in big city hospitals.

I came into this work because I kept seeing the same pattern: Women, especially older women, were neglected in health research. Issues that are highly relevant for older women, such as menopause, were under-researched and even taboo to discuss. But it’s not just about menopause. It’s a system not paying enough attention to women, especially women who aren’t wealthy, who don’t have perfect access to healthy food, safe exercise, or regular specialist care.

My work focuses on prevention, self-efficacy, and access — particularly for older women and underserved communities.

2. What sparked your interest in focusing on peri-menopausal and menopausal women specifically?

Women are underrepresented in research on chronic disease, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease, so we actually don’t have enough sex-specific, menopause-specific guidance for prevention. I focus on midlife and older women because it is a time in life when: (1) biology is changing, (2) life responsibilities are changing, and (3) the system isn’t tailored to address these needs in isolation and certainly not in a holistic manner. Moreover, the gap is particularly pronounced for older women, women on low incomes, and women residing in rural areas, who may face additional challenges.

3. What are some of the biggest challenges women face in managing their health during this stage of life?

There is a couple come up when I talk with women:

-

Time and caretaking: Midlife women are often supporting teenagers, ageing parents, and sometimes partners with health issues, and working. Their own health becomes “later,” and “later” turns into five years.

-

Not being believed: Many women tell me they raised concerns, sudden belly weight, brain fog, mood swings, sugar spikes, and were told “that’s just menopause.” Being dismissed delays prevention and increased risk for chronic disease and other health issues.

For women in lower-income or rural settings, add cost, transport, and fewer local services on top of all that.

4. How do lifestyle factors - like diet, exercise, stress, and sleep - play into the risk or management of diabetes for women in midlife?

Yes, lifestyle factors matter at any age and stage of life. For mid-life and older women, the issue can often be finding the time to attend to their health needs in the midst of caring for others and working. Likewise, exercise programs, like many other health programs, are often designed and implemented without explicitly considering the needs and preferences of women. This is why co-design research is vital for understanding what matters most. Similarly, women are not a homogeneous group; there is a lot of diversity across individuals and programs/interventions need to have the flexibility to cater to a wide range of needs. This is one of the reasons our research at CHRI is designed in keeping with principles of universal design and is typically tailored to the needs of specific groups through co-design.

5. How important is community support and connection for women trying to manage their health at this stage?

Community and structural support are critical. We need to change the systems that make it difficult for women to access health and prevention interventions.

People of all genders need connections with others. But everyone is different and has different needs and preferences. For example, if you take exercise, any individual woman may prefer group-based activities, while others prefer to exercise independently. It is about creating programs and services that can flexibly meet individual needs. People appreciate and need choice.

6. What have you learned from talking with women in the community about their experiences with menopause and metabolic health?

Often, women say they feel blamed. They’re handed generic advice and little structural support.

We need practical, local, respectful support to help women manage their health, and we need health messaging that stops treating women like they’re a problem to be fixed and starts treating them like partners in prevention.

7. Can you tell us about the kind of research you’re doing right now, and what questions you’re trying to answer?

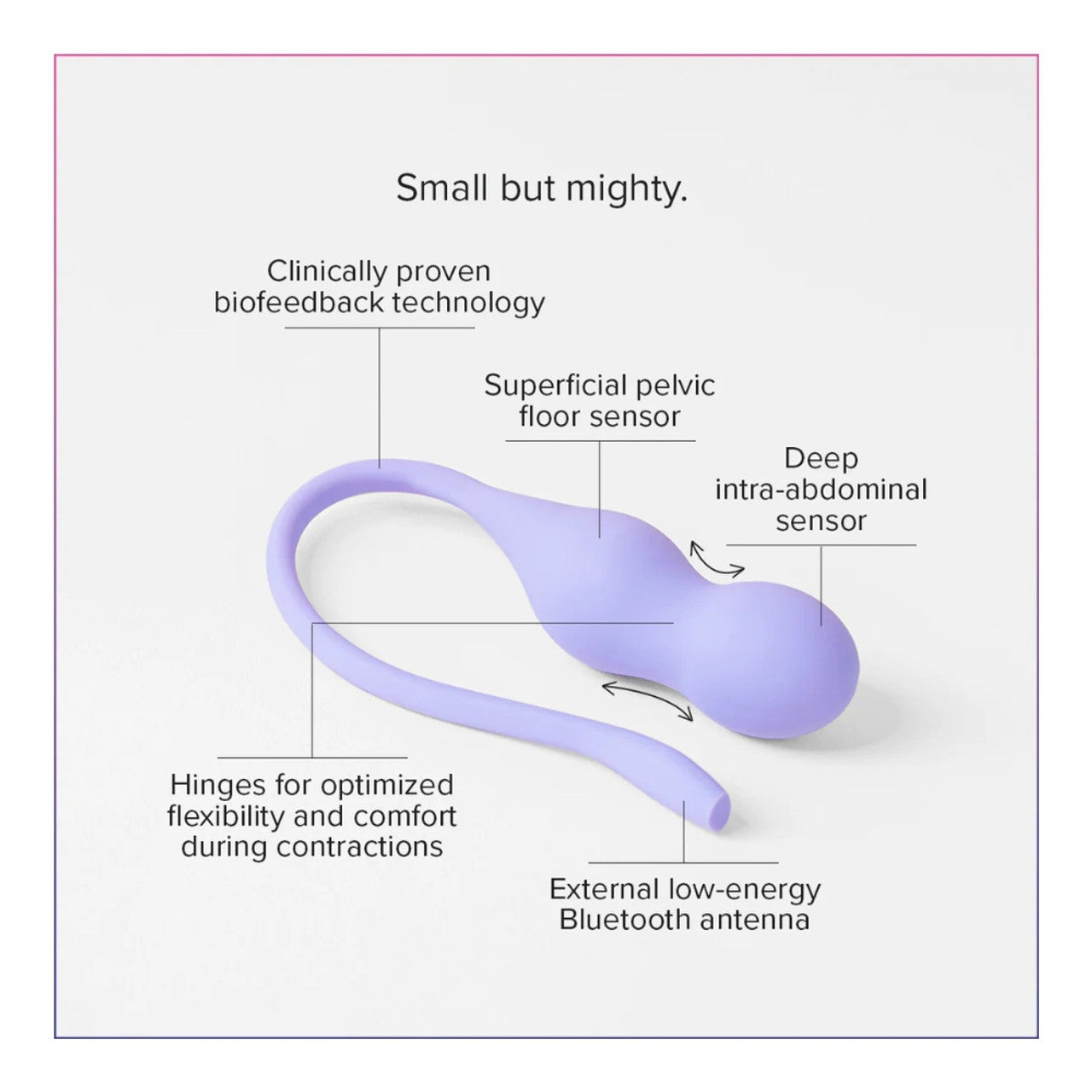

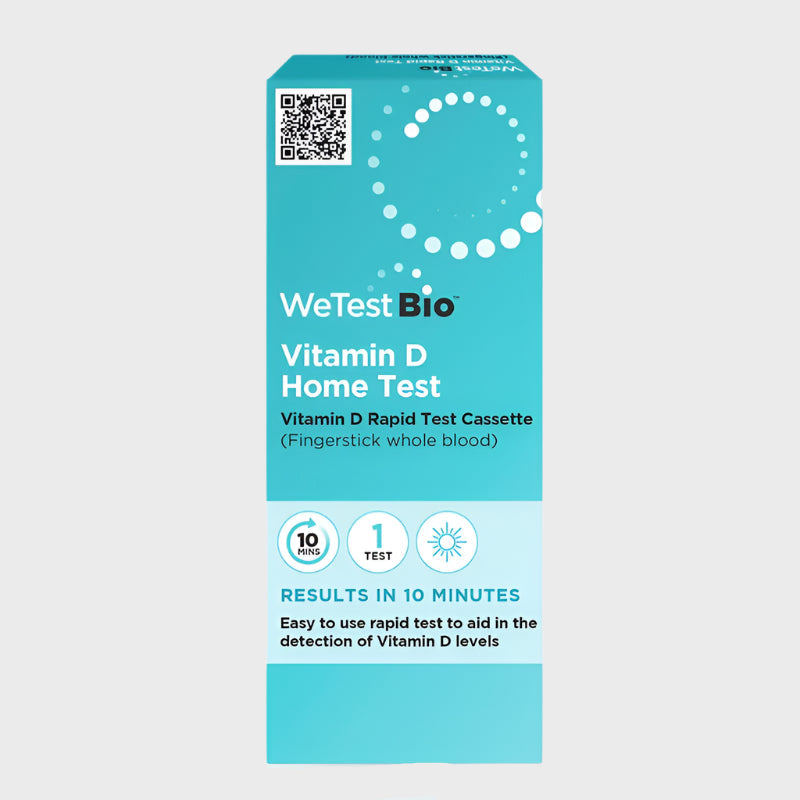

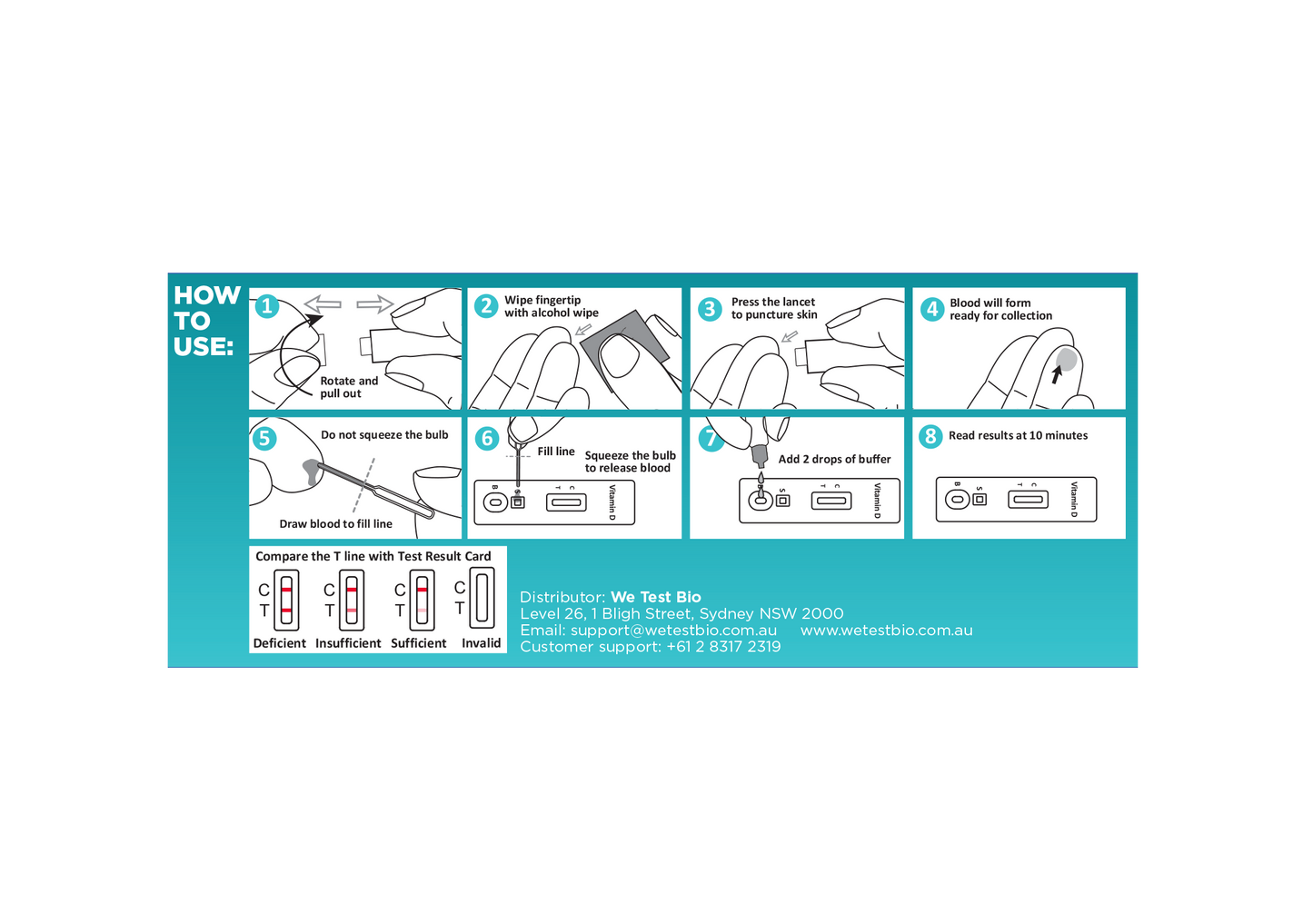

Right now, we’re doing community-based research with older women and people in small or underserved towns as well as diverse cohorts in urban locations. We co-design programs often using digital tools that help women see their own health data — things like activity, HR, glucose patterns, mood, sleep — and understand what’s changing for them personally, not just “the average patient.”

A big focus of our planned research is: How can we use wearable tech and simple monitoring to catch metabolic risk earlier, when it’s still reversible, and then support women to act on it in a way that fits their real lives (budget, culture, transport, caring roles)?

We’re also working on models where the community itself — not just clinicians — helps shape prevention programs. That’s important for equity because most mainstream programs are designed for middle-income, city-based, English-speaking, already health-literate women, or are more likely to be designed for men.

8. What’s one of the most surprising or interesting things you’ve discovered through your work so far?

If you show women their own data in a respectful way, they are interested and they get strategic about their health.

For example, when women can actually see how much they move, they start making micro-adjustments that add up. They need feedback that’s specific, timely, and judgment-free.

Also: women are hungry for menopause-specific metabolic information. They’re not just asking, “How do I stop hot flushes?” They’re asking, “How do I not end up diabetic at 62 like my sister?” We really need the system to catch up with what women want and need.

9. How do you make sure your research findings are shared in ways that are useful and easy for women to understand?

The most important thing we do is involve women in our research. We co-design with people who will actually use the information we anticipate from the research. This includes women with lower health literacy, omen who speak languages other than English, and women with diverse cultural backgrounds.

10. How do cultural, social, or economic factors affect women’s ability to access diabetes care or information during menopause?

Health is completely intertwined with cultural, social and economic factors. Just a few that can have a huge impact are:

-

Cost: Healthy food, gym access, private specialists, CGMs or wearables — these are not equally affordable.

-

Time and transport: If you’re in a rural or remote town, services may be physically far away.

-

Language and trust: Health information is often written for university graduates, not for real-world women who are busy, stressed, and don’t have time to decode jargon.

All of that means the women at highest risk often get the least tailored care. That’s an equity failure, not an individual failure.

11. What can be done to make research and health programs more inclusive for women from different backgrounds and communities?

Three things we need to fix:

-

Include women properly in clinical research.

Women — especially older women — are still underrepresented in many cardiovascular and metabolic trials, even though cardiometabolic disease is a leading cause of death in women.

If women aren’t in the trials, the guidance doesn’t fit women. -

Design with, not for.

We use co-design: women from the target community help shape the questions, language, tools, and measures from day one. That’s especially important for culturally diverse, low-income, and rural/remote women. -

Meet women where they are.

That can mean offering group sessions or education in community centres instead of hospitals, using audio or conversational formats instead of long written forms, and respecting caregiving schedules.

12. What changes would you like to see in how we talk about or approach women’s health around menopause?

I’d like us to stop treating menopause as just “symptoms to silence” and start treating it as an opportunity to recalibrate our efforts and realise this is a time for women to focus on their health broadly.

When a woman in her late 40s or 50s walks in saying, “Something’s changing,” that’s not only a quality-of-life issue. It can be a warning sign for future diabetes, cardiovascular disease, bone health issues, and cognitive decline.

I want routine menopause care to include metabolic screening, strength/mobility assessment, and real conversations about sleep, stress load, and recovery.

13. How do you see your work helping to improve prevention or management of Type 2 diabetes for women in the future?

My aim is early warning plus practical support.

Suppose we can identify women who are at risk of developing insulin resistance in their late 40s and early 50s and provide them with tools they can realistically use in their own environment. In that case, we can delay or even prevent Type 2 diabetes. We already have evidence that targeted lifestyle changes, improving muscle strength, and managing visceral fat can substantially reduce the risk in midlife women, not just for diabetes but also for other chronic diseases.

For me this is about shaping the curve before a woman is “diagnosed,” especially for women who traditionally fall through the cracks: rural women, low-income women, culturally and linguistically diverse women, and older women who didn’t grow up being told their health mattered.

14. If you could give one piece of advice to women who are peri- or menopausal who are concerned about their health, what would it be?

Take yourself seriously.

If something feels off, such as energy, sleep, weight around the middle, mood swings, sugar crashes after certain foods, that is essential data.

Ask for proper metabolic screening (blood glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, lipids). Ask about sleep. Ask about stress. Ask about muscle strength.

And if you’re brushed off, ask again, or find a practitioner who takes you seriously. Advocate for yourself like you would for someone you love.

15. If you could give one piece of advice to women who are concerned about their health, what would it be?

Don’t wait for crisis care.

Menopause is not the end -- it’s the start of the next 30–40 years of your life. You deserve active prevention. Advocate for yourself.

16. What’s next for your research or projects in this area?

Next, we’re expanding our work in urban areas with women from a broader range of backgrounds and with small and remote communities. We’re building models where women can:

-

access their own health data in plain language,

-

set goals that actually match their lives,

-

get peer support, not judgment,

-

and feed their lived experience back into research and service design.

17. How can people learn more about your work or get involved?

We partner directly with communities, local services, and women with lived experience.

Our work always includes consumer and community advisory groups. Women with real-world experience are not “focus group quotes” to us; they’re part of the research team. Anyone interested in learning more about our research can sign up to become a member of our consumer user panels. Participants provide opinions and ideas that help shape and govern our research. https://chri.au/#join-our-consumer-user-panel

18. Is there one key message you’d like listeners or readers to take away from this conversation?

Women in midlife and older life deserve proactive, respectful, evidence-based support to prevent diabetes and other chronic diseases and protect long-term health.

Dr Connie Henson, Senior Research Fellow at CHRI (Co-Design Health Research & Innovation) at UNSW.

Connie has not one, but two PhDs, in Psychology and Health Systems & Populations.

Connie's research has focussed on digital health equity and system change, particularly for priority populations, including older adults, women, and people in underserved and remote communities. She leads co-designed studies that explore the use of wearable technology, digital platforms, and inclusive health models to promote access, engagement, and wellbeing.